From Confusion to Coalition: Why publishers must join the responsible AI movement

AI is no longer knocking at the door of academic publishing. It’s already inside, reorganizing our systems, decisions, and even ethics. While AI offers unprecedented opportunities for efficiency and innovation, its unchecked and fragmented implementation raises serious ethical concerns, leading to a growing number of retractions and a palpable sense of unease within the scholarly community.

Why Current AI Adoption is Alarming

While the recent STM recommendations classified the use of AI in manuscript preparation, it highlighted the urgency to establish consistent standards. The role of AI in publishing has expanded dramatically, especially with the advent of powerful Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. Furthermore, studies have revealed their role beyond mere data analysis and plagiarism detection, promising their role as active participants in the creating and evaluating scholarly content. This finding is further reinforced by the 2024 Oxford University Press survey which revealed that almost 76% researchers have used AI in their research.

A thematic analysis of publisher guidelines reveals a broad consensus: while AI can be a valuable tool, it cannot be credited as an author because it cannot take responsibility for its output. However, the rapid and often unregulated adoption of Gen-AI has introduced a new category of academic misconduct. Cases involving “paper mills,” have increased due to AI misuse. Over 89% papers were retracted due to the use of AI (15% fraudulent papers due to the use of AI and 74% genuine research distorted due to the use of AI) based on Retraction Watch data retrieved on 6th June, 2025.

Although prohibition of AI as an author is a common thread, publisher remain inconsistent in polices regarding AI disclosure, and the use of AI-generated data and images. This lack of harmonization creates confusion for authors and reviewers and makes it challenging to enforce ethical standards across the board.

The Alarming Nature of Fragmented Policies

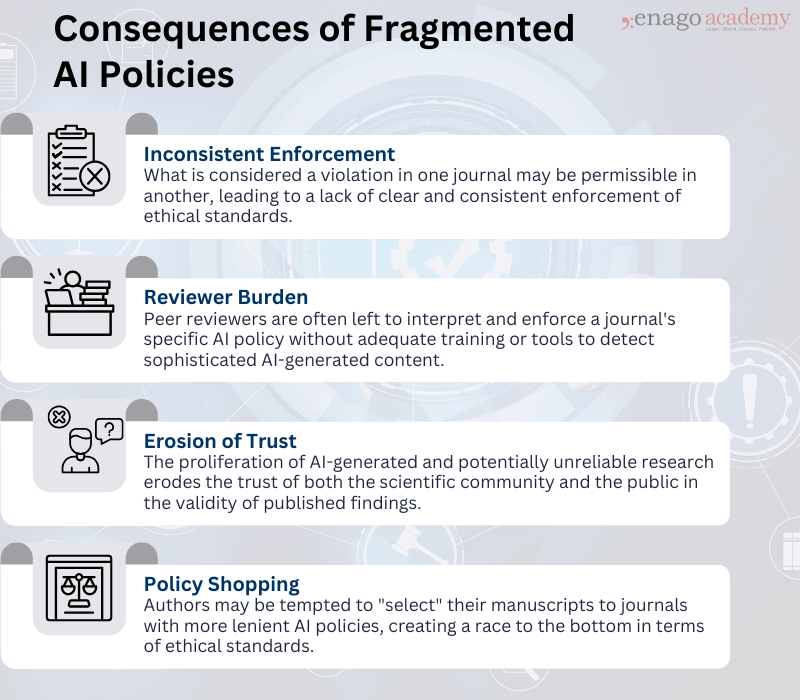

While most journals agree on prohibiting AI from claiming authorship, they diverge widely on defining acceptable AI use. Some insist on disclosing AI tools used in writing, but many omit clear rules for AI-generated data, images, or translations. This lack of standardization, spanning definitions, disclosure thresholds, tool scope, and oversight, creates a confusing patchwork that leaves authors, reviewers, and editors uncertain about what constitutes ethical AI use. As a result, these divergent approaches undermine trust in the scholarly record and open the door to inconsistent enforcement.

This patchwork of regulations leads to several alarming consequences:

While the potential for innovation is undeniable, the current state of fragmented policies and alarming instances of misuse serve as a stark warning. Publishers, as the stewards of the scientific record, have a critical and urgent responsibility to move beyond a reactive stance and embrace a proactive, collaborative, and ethically grounded approach to governing the use of AI.

Why Publishers Must Lead the Responsible AI Movement

In this volatile environment, publishers must take the lead. This isn’t optional, its necessary, especially when public trust towards research is already fragile. The perception that research is being generated, reviewed, or validated by unaccountable AI systems will only accelerate its erosion. Furthermore, every instance of opaque AI use, every retraction due to AI misuse, chips away at the credibility of the entire publishing enterprise. Rebuilding that trust will be far more difficult than safeguarding it now.

To move forward, we need a unified framework built on a clear set of principles. This framework must:

1. Standardize AI Disclosure Requirements Across the Research Lifecycle:

To preserve transparency and accountability, publishers must implement a shared set of disclosure norms that require authors, reviewers, and editors to clearly state how AI tools were used—whether for language refinement, data visualization, analysis, or manuscript drafting; and if the AI-generated output was vetted by a human expert. These standards must specify:

- What must be disclosed (tool name, function, version, usage stage, prompts (if applicable))

- Who is responsible (author, reviewer, editor)

- When disclosure is required (at submission, revision, or acceptance)

Furthermore, they can consider developing a centralized AI disclosure templates integrated into journal submission systems and editorial workflows.

2. Create a Cross-Functional Classification Framework for AI Use

Current guidelines focus on broad aspects like writing, editing, image generation, etc. Establish clear, standardized categories for how AI is used in manuscript preparation, ranging from basic language correction to full-scale content generation. A broader classification framework can categorize AI involvement across:

- Manuscript preparation and content generation

- Content summarization

- Manuscript editing

- Data and image creation, editing, and modification

- Text translation/localization

- Peer review and editorial assessment

Each use case must be supported by concrete examples, gray-zone scenarios, and contextual guidance for responsible application. Furthermore, publish a standardized AI-use taxonomy, adaptable by discipline, and constantly updated as technology evolves.

3. Mandate Radical Transparency in all AI-influenced Workflows:

Disclosure, both in terms of AI use and review of the AI-generated output, must be non-negotiable and comprehensive. The use of generative AI or AI-assisted technologies must be clearly declared at every stage; as readers have a right to know how the research they are consuming was created and vetted. To enable this:

- AI use must be required to be disclosed at all stages of the publishing pipeline

- Audit trails must be captured within editorial systems

- Public-facing “AI Use Statements” should accompany published work

Also, introduce traceable AI disclosure logs and visible “AI declarations” in final publications. This can be similar to conflict of interest or data availability statements.

4. Guarantee Human Oversight at Every Critical Decision Point:

AI must always be a tool to augment, not replace, human judgment. To ensure this:

- All authorship, peer review decisions, and editorial rulings must be validated by qualified human professionals

- Final acceptance decisions should occur at AI-free checkpoints

- Any AI-generated recommendation must be audited and contextualized by a human editor or reviewer

Recommendation: Embed mandatory human oversight in all high-impact decisions, with editor/reviewer training modules to spot and assess AI misuse.

5. Collaborate and Promote Inclusive AI Governance and Literacy

Require diversity impact assessments for AI tools. Prioritize inclusive, multilingual datasets and partner with regional stakeholders to evaluate tool fairness and accessibility. Furthermore, collaborate with research institutions and funders to develop aligned policies, shared ethics training programs, and industry-wide certification for Responsible AI in Research Practices. Lastly, convene cross-publisher alliances to co-create and endorse a “Responsible AI in Publishing Charter” that is globally applicable, culturally inclusive, and technology-responsive.

Publishers can consider partnering with Enago’s Responsible AI Movement, which is already promoting the responsible use of AI tools and educating authors on best practices, to ensure our frameworks are practical and globally relevant.

Toward a Shared Industry Charter

The time for siloed efforts is past. An industry-wide “Responsible AI in Publishing” movement can redefine the adoption of technology in publishing. As we stand at a watershed moment, we can continue down the current path of fragmented policies and growing distrust, or seize this opportunity to build a more robust and ethical future for scholarly communication.

The vision is simple: responsible AI use must become the new baseline; a shared expectation, not a competitive differentiator. This is more than a policy challenge; it is a cultural one. The question for every publisher is no longer whether to act, but how soon and how well. The future of trust in scholarly communication depends on it.