Why Converting Manuscripts Between APA and Harvard is Harder Than It Looks

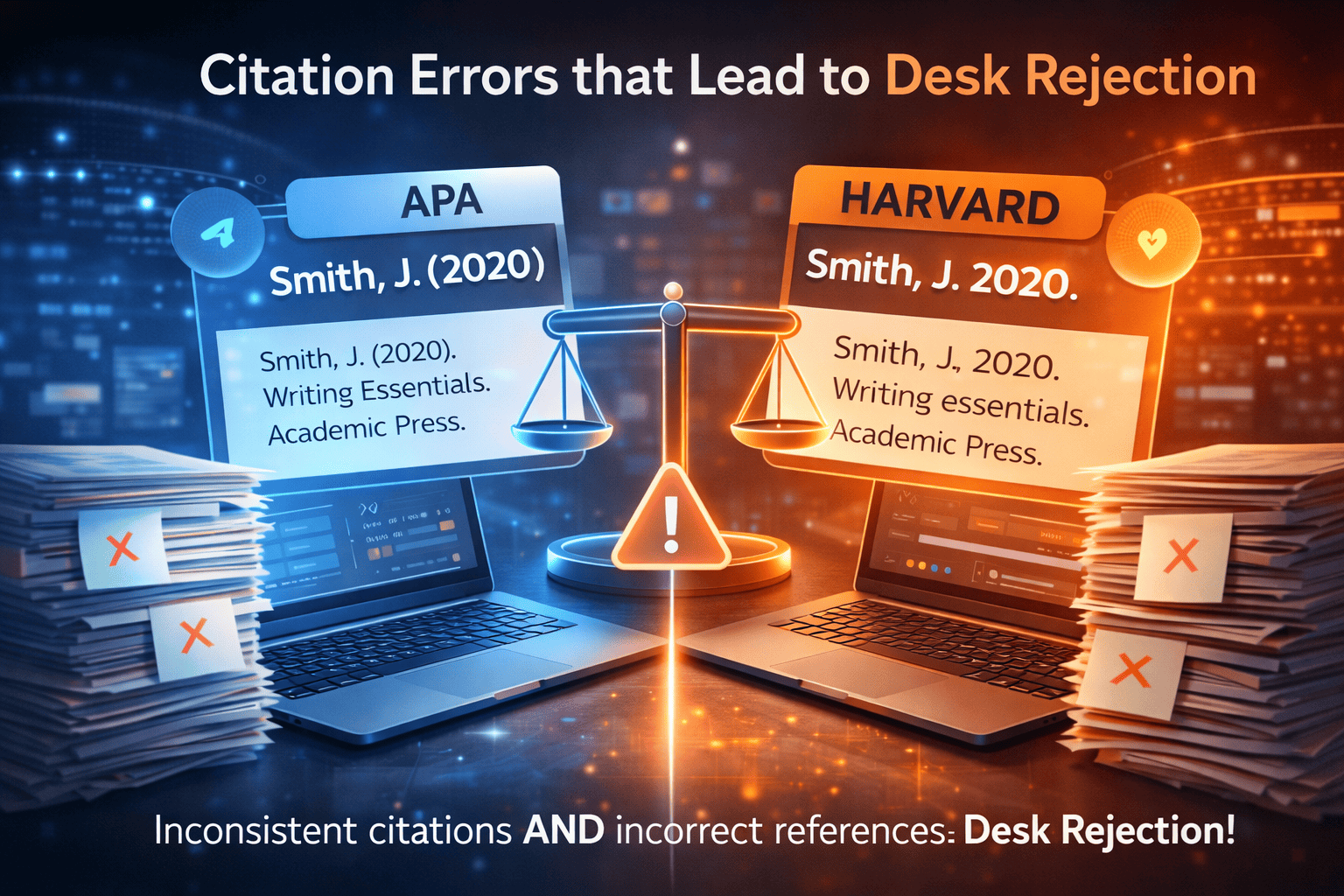

A surprising share of submissions are rejected at the editorial screening stage because of technical or formatting noncompliance – problems that often begin with inconsistent citations and reference lists. Recent publisher data and editor surveys describe desk-rejection rates in “the tens of percent” for manuscripts that fail basic submission checks, underscoring why correct referencing matters as much as good science.

This article explains why converting between APA and Harvard is deceptively difficult, focusing on how in-text citations, reference-list structure, and punctuation/capitalization rules diverge. It also outlines practical, step-by-step strategies researchers can apply to convert reliably and avoid common pitfalls when preparing manuscripts for submission.

What the Two Systems Share — and Where They Diverge

Both APA and Harvard use an author-date system: readers locate short parenthetical citations in the text and trace full details in an alphabetized end-list. This shared architecture makes superficial conversion feasible. However, “Harvard” is not a single, formal standard the way APA is; many institutions publish their own Harvard variants (for example, individual university versions), and these differences drive much of the conversion friction.

APA (current: 7th edition) is a formal manual with prescriptive punctuation, capitalization, DOI/URL rules, and explicit treatments for electronic sources, multiple authors, and up to 20 authors in reference entries. Harvard systems generally follow the author-date principle but vary in punctuation (commas vs. spaces), publisher-location conventions, capitalization rules, and whether retrieval dates or “Available at:” phrases are used. The variability within Harvard is often the single largest obstacle to reliable, repeatable conversion.

Why the Date Position and Its Formatting Matter More Than It First Appears

In both systems, the date signals currency, but APA emphasizes the date visually and syntactically: the year appears in parentheses immediately after the author in both in-text citations and reference entries (e.g., Smith, J. (2020.)). This consistent placement supports quick scanning of how recent the cited literature is and makes date-based synthesis (e.g., trend analyses in literature reviews) easier for readers and reviewers. APA’s rules about including the year with abbreviated author citations and in narrative constructions also standardize tense choices (past vs. present perfect) in literature synthesis.

Harvard styles also use author-date cues in text (e.g., Smith 2020), but because Harvard is a family of styles, the exact punctuation and the way the date is presented in the reference list can differ (Smith, J., 2020. vs Smith, J. (2020.)). Those small surface differences have outsized consequences: automated checks, reference-parsing software, and editors trained to expect a specific house style can flag even consistent but differently punctuated lists as incorrect. The end result is extra revision cycles and potential delays in peer review.

Concrete Differences That Cause Most Conversion Headaches

- In-text punctuation and conjunctions: APA uses a comma between author and year in parenthetical citations and an ampersand (&) between two authors in parenthetical form; Harvard variants commonly omit the comma and use “and” rather than “&.” Converting every instance of (Smith, 2020) to (Smith 2020) or vice versa is tedious and error-prone across a long manuscript.

- Reference entry structure: APA places the year in parentheses immediately after author names and uses sentence case for article and chapter titles while keeping journal names in title case and italicized; many Harvard guides prefer different punctuation (commas/periods), sometimes use title case for titles, and can include publisher location or “Available at:” prefixes for URLs. These formatting differences cascade: capitalization changes, punctuation swaps, and DOI/URL formats require careful, manual correction unless automated reliably.

- Treatment of multiple authors: APA now lists up to 20 authors in a reference entry; Harvard variants often truncate earlier or have alternative rules for “et al.” This affects reference length and the ordering logic editors expect.

- DOIs, URLs, and retrieval dates: APA 7 treats DOIs and URLs as hyperlinks and removes labels such as “DOI:”; it also instructs retrieval dates only when content is likely to change. Harvard guidance varies: some Harvard styles require “Available at:” and an access date for web content. These subtle differences change both readability and compliance with journal instructions.

Practical Consequences for Scholarly Writing and Publishing

Inconsistent or incorrectly converted citations can affect peer review in several ways. Editors and reviewers may interpret inconsistent referencing as carelessness, potentially biasing their evaluation of the manuscript. Reference parsing tools used by publishers can fail to match references to DOI metadata, causing administrative delays. Incorrect formatting can result in desk rejections or requests for resubmission after line-by-line corrections, extending time to publication. Given the measurable editorial sensitivity to formatting, accurate conversion is a pragmatic part of publication strategy.

A Step-by-Step Approach to Convert Consistently

- Identify the target house style exactly (APA 7 or which Harvard variant) and collect the publisher’s “Instructions for authors.”

- Export the reference database from your reference manager (EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley) in a neutral format (RIS/BibTeX).

- Apply the target citation style in the reference manager and regenerate the reference list; then manually inspect the first 20 entries for edge cases (conference papers, chapters, preprints).

- Use a citation-format validator or formatter to catch punctuation and DOI/URL differences; review and accept changes in tracked format.

- Manually search and correct remaining anomalies (capitalization, edition statements, publisher location, “et al.” rules).

- Run a final textual pass to adjust in-text citations (commas/ampersands) and to ensure narrative references use the correct tense and punctuation.

For quick reference, these steps are best performed in this sequence because changes in the reference list typically require corresponding changes in the in-text citations.

Tools and Services That Ease the Conversion Burden

Reference managers (Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley) are the first line of defense because they can switch style templates quickly, but they do not always implement every local Harvard variation correctly. Newer automation tools – for example, citation formatters that validate references against publisher metadata and transform lists between styles – reduce manual effort and catch missing elements such as DOIs or incomplete author lists. Trinka’s Citation Formatter and similar tools automate large parts of style conversion and validation, saving hours on long reference lists.

When to Consider Professional Help

If the manuscript has hundreds of references, if the target journal’s house style includes unusual deviations, or if multiple co-authors have contributed mixed-format references, professional copyediting and reference-formatting support can reduce risk of desk rejection and speed final submission. Services that provide manuscript editing and reference formatting not only standardize punctuation and capitalization but can also validate citation integrity and suggest fixes for secondary referencing issues. Enago’s manuscript editing and formatting services describe such reference-formatting and compliance support for authors preparing submissions.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Converting Styles

- Blind global replace: changing “(Smith, 2020)” to “(Smith 2020)” across the document without checking narrative citations or ampersands can introduce errors.

- Ignoring publisher guidance: journals often publish a narrow house variant of Harvard or APA; matching that exact variant avoids revision cycles.

- Overreliance on citation generators: many online generators produce inconsistent punctuation or omit DOIs; always validate against the source.

Conclusion: Practical Next Steps for Authors

Accurate conversion between APA and Harvard matters because small stylistic differences reverberate through editorial workflows, automated checks, and reviewer perceptions. To reduce risk:

(1) identify the exact target variant,

(2) use a reference manager as the control point,

(3) validate with an automated formatter, and

(4) apply a short manual quality check for edge cases.

When references are numerous or the manuscript is time-sensitive, consider professional manuscript editing or reference formatting support to ensure consistency and compliance and to reduce avoidable delays. Enago’s editorial and formatting services and tools such as Trinka’s Citation Formatter can help streamline these steps and prepare the manuscript for a smooth submission.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between APA and Harvard citation styles?▼

Both use author-date format, but APA is a formal standard with prescriptive punctuation, capitalization, and DOI rules. Harvard is a family of styles with variations in punctuation (commas vs. no commas), capitalization, and URL formatting. APA uses commas and ampersands in citations; Harvard often uses 'and' without commas.

Can I use find-and-replace to convert APA to Harvard citations?▼

No, blind global replace is dangerous. Converting '(Smith, 2020)' to '(Smith 2020)' without checking narrative citations, ampersands vs. 'and,' reference list punctuation, capitalization rules, and DOI formatting will introduce errors. Manual verification after automated changes is essential.

Why does Harvard citation style vary between journals?▼

Harvard is not a single formal standard like APA. Individual universities and publishers create their own Harvard variants with different punctuation rules, capitalization preferences, publisher location requirements, and 'Available at:' URL formatting. This variability makes consistent conversion difficult.

How do I handle multiple authors in APA vs Harvard?▼

APA 7 lists up to 20 authors in reference entries and uses ampersand (&) in parenthetical citations. Harvard variants often truncate earlier with 'et al.' and use 'and' instead of ampersand. The exact rules vary by Harvard version, requiring careful attention to target journal requirements.

Do reference managers automatically convert between APA and Harvard?▼

Reference managers can switch style templates, but they don't always implement local Harvard variations correctly. After automatic conversion, manually inspect the first 20 entries for edge cases, check punctuation, verify DOI formatting, and validate capitalization rules against specific journal guidelines.

What causes desk rejection related to citation formatting?▼

Inconsistent citations signal carelessness to editors, causing desk rejections before peer review. Reference parsing tools fail to match incorrectly formatted entries to DOI metadata, creating administrative delays. Desk-rejection rates reach 'tens of percent' for manuscripts with basic formatting noncompliance.